MATT BOTTRILL

Endura’s grassroots champion

FAMILY AFFAIR

Cycling is a small but rewarding world in which, sooner or later, your path crosses with that of everyone else in its midst. I had wanted to interview Matt Bottrill for years. Now, tasked by Endura with recording his remarkable story, my opportunity had arrived.

It’s hard to think of a rider better qualified to carry the Livingston brand’s famous arrow than one dubbed ‘the people’s champion’ by the cycling media. The setbacks Bottrill experienced in a riding career that climaxed with an annus mirabilis which, in 2014, made him virtually unbeatable in the time-trial, are as intriguing as his successes.

“Endura is a family business. We’re a family business. They’re not just concerned about Matt Bottrill the athlete, they care about the person, too.”

Bottrill was the gifted espoir, so talented he was once placed on the same pathway as Sir Bradley Wiggins, but whose career derailed during his time with British Cycling, rather than advanced. Thirteen years later, while Wiggins was winning the Tour de France, Bottrill was delivering the post in the East Midlands town of Coalville, where he grew up.

A father-of-three with a full-time job, he found inspiration in necessity, and with just eight hours a week for training, made a specialism of the time-trial. With a stationary bike for training, an aerodynamicist of rare insight to hone his position, and a “crazy fast” skin suit, whose advantage he estimates at ten watts, Bottrill dominated domestic time-trialing in a season whose impact is still felt today.

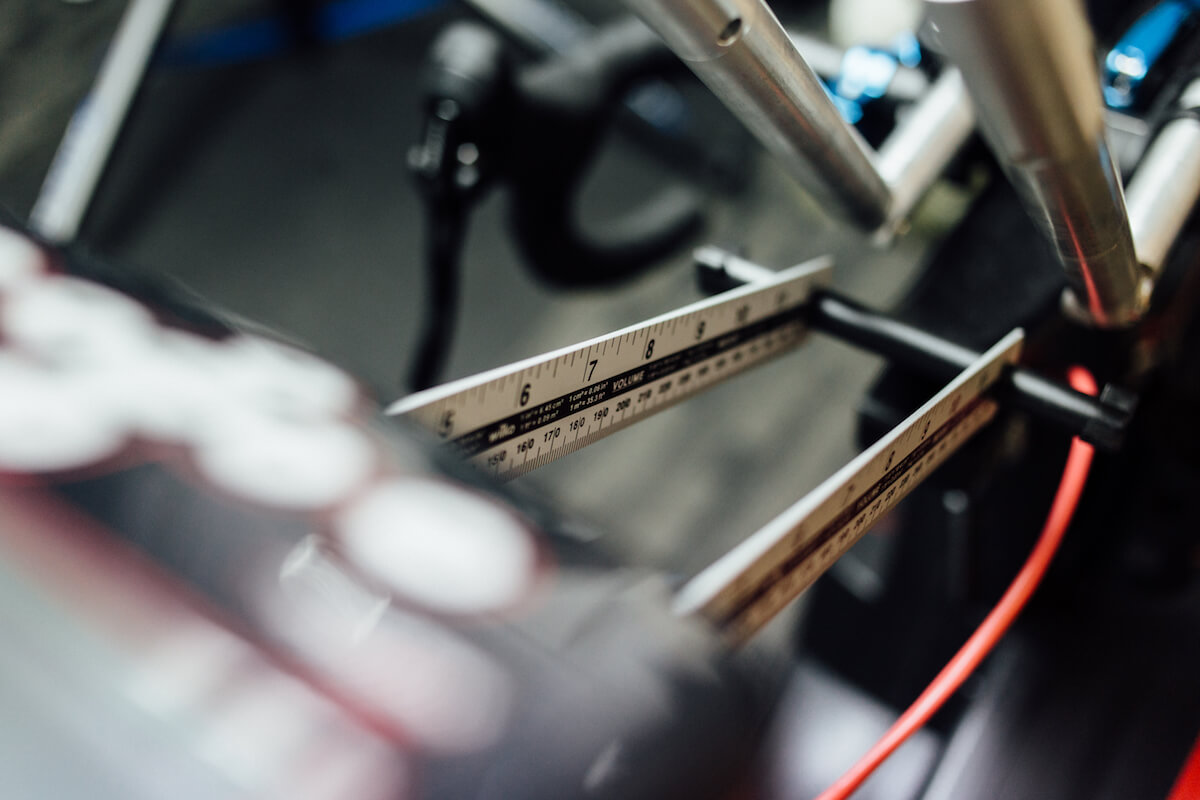

The skin suit, needless to say, was made by Endura. The aerodynamicist was Drag2Zero’s Simon Smart. The wind tunnel was, and remains, the headquarters of Drag2Zero, the test lab for Endura’s aero projects, and the property of the Mercedes-AMG Petronas Formula One team.

“Endura could see that I was passionate about the brand from the feedback I was providing,” Bottrill says. “They’re a family business. We’re a family business. We get it. They’re not just concerned about Matt Bottrill the athlete, they care about the person. I feel part of the company; part of the family. That’s how Endura is run. It is like a big family, and we’re very much the same.”

THE RACE OF TRUTH

The time-trial is arguably cycling’s most complete discipline. It is certainly the toughest. There is no adrenaline to dilute the pain; no transcendent moment of glory for the winner as he crosses the finishing line.

Suffering - and to the very last pedal stroke, for those who have mastered the art - is all that is on offer. There is no opportunity for exultation, no throwing of arms in the air. Quiet satisfaction, once the searing pain of oxygen debt has died away, is as good at it gets.

“Time-trialing has become a discipline where every element counts. To ride a time-trial fast now is like Formula One racing, it’s become that much of an art."

It’s well known that time-trialists are cycling’s biggest ‘engines’, but their skill and technique is less frequently acknowledged. The best approach the course as an exercise in efficiency. Every climb, every corner, must be optimised. The margins are impossibly fine, and for one, simple reason: the riders are already on the limit. The time-trial is closer to art form than sporting endeavour.

Then there is the equipment. A time-trial bike is one that stops the causal punter in his tracks. The deep section wheels, the low-profile base bar and ‘ski’ extensions - it is a study in sleek design. And then, of course, there is the clothing: the skin suit is the greatest ‘mechanical’ advantage a time-trialist can buy; the garment that affects 80 per cent of the aerodynamic picture. But here we get ahead of ourselves.

Matt Bottrill knows a thing or two about winning time-trials. His opinion is of such value that Endura sought it repeatedly during the development of the D2Z Encapsulator suit. He talks of drag coefficients and power zones; of developing new techniques in training and implementing them in races; of "laying down the power", and the importance of choosing the right moment to do so.

In every instance, Bottrill talks of how each element is required to ride a time-trial fast. He makes the distinction regularly, but without emphasis; almost unconsciously. The implication is that riding a time-trial merely to take part is a comparatively simple affair. To ride fast is a different matter entirely.

LEARNING CURVE

Bottrill was for so long deprived of victory that he earned the nickname, ‘The Bridesmaid’. By 2010, he’d had enough. Third and fourth-placed finishes were no good to a rider who, as a road racer, had been crowned British under-23 champion and won rounds of the Premier Calendar.

Bottrill’s need to win national time-trials had taken on a genuine emotional significance, and he reached out for new technology by making contact with Bob Tobin of Cyclepowermeters. Bottrill, once on the wrong end of training presented as scientific, was about to embrace the revolution.

"In 2014, the advantage I had over everybody else was that I was wearing Endura suits. The advantage was massive; we're talking ten watts."

“I sent Bob a cheeky email and said: ‘Look, I’m going to be honest with you: I can’t afford coaching, but if you can train me, and enable me to use this power meter, I can repay you with exposure on social media.’ Luckily, he made the trade off. He introduced me to Simon Smart, and that’s where it all kicked off.”

Bottrill’s learning curve might be as steep as any he encounters in the data of the world class athletes who now depend upon his coaching services. The boy with too much energy to be contained within a classroom, and who left school with a grade F in mathematics, was about to strike up a highly productive friendship with an aerodynamicist who’d made his name in sport’s ultimate technical showcase. Formula One’s loss would be Bottrill’s gain.

In Smart, Bottrill had found an aerodynamicist tired of the limitations placed on engineers by Formula One regulations, and with a powerful interest in cycling. In return, Smart gained the privilege of working with one of the finest time-trialists this country has produced. Not that Bottrill, always a force against the watch, had ever dreamed of being a ‘tester’.

“There’d always been a divide between roadies and ‘testers’, where ‘testers’ were these simple creatures, who’d go out and destroy themselves. But time-trialing now is a discipline where every element counts. To ride a time-trial fast is now like Formula One racing, it’s become that much of an art.”

PAIN GAME

Science is no substitute for pain. A power meter will record a rider’s effort, but a willingness to explore his deepest reserves is still a must. Even a position developed beneath the expert eye of Simon Smart will not negate the need to ride to exhaustion.

For Bottrill, and those of his ilk (Alex Dowsett and Graeme Obree, to name only two who have featured on this website), the ability to ‘go deep’ becomes a matter of necessity, and perhaps even a badge of pride. It is the distinguishing feature of a world class athlete, according to Bottrill, and more than a purely physical matter.

"It doesn't matter how hard you've trained, if you can't dislodge that pain barrier, then you're going to finish seconf. But if you can..."

He speaks of “training Matt” and “race Matt”. One has the ability to access the darkest moments in his life to produce exceptional performances. It comes as a revelation from such a positive force - a coach to some of the biggest stars in triathlon, and an inspiration to the young riders of his new team - but Bottrill is a more complex character his Twitter feed potrays.

“‘Race Matt’, when he’s in pain, is touching on emotions; things that have happened to me. That’s why world class athletes are so good at what they do: when it comes to that final bit, they can touch on something, and they can go through it.

“That’s what makes me able to do what I can. When it comes to that last phase, it doesn’t matter how hard you’ve trained, if you can’t dislodge that pain barrier, then you’re going to finish second. But if you can…”

He leaves this last thought hanging. We can add another piece to our time-trial jigsaw. Pacing, power, position…none by themselves, or even taken as a whole, are enough to make the difference in cycling’s loneliest discipline. The rider must be willing to access his most deeply held emotions if he is to separate himself decisively from the opposition.

GRIEF AND TRIUMPH

In 2014, Bottrill’s season of seasons, the loss of his late grandfather, and a burning desire to do justice to his memory, became a powerful motivation. The old man had seen his grandson achieve much in the year before his passing, including a second place to Dowsett in the British time-trial championships, but Bottrill had tired of second places. Determined to turn near-misses into victories, and, above all, to win the national 25-mile title, Bottrill’s grief became an unquenchable fire.

His relationship with his grandfather defined his riding career, to a very large extent. He had introduced him to the sport, after all, turning a troubled 12-year-old into a competitive force. With parents and teachers exhausted by Bottrill’s inexhaustible presence, and home and the classroom proving inadequate vessels in which to contain the boy’s insatiable energy, the bike suddenly provided all the answers. Bottrill had his grandfather to thank.

"When I talk about mindset, I've been to some dark places, but in 2014, I was invincible. No one could touch me. It was for my grandad."

Ask him to describe the effect of the bicycle on his younger self, and Bottrill is frank: "It was life-changing.” He admits that he struggled with school, and describes himself as un-academic, even if he now earns a living from an understanding of power zones and drag coefficients.

At an age where numbers were anathema, however, cycling was Bottrill’s ultimate learning experience. The man who had steered him towards this two-wheeled classroom took on a profound significance. The grief of his passing provided the rider with an inexhaustible fuel source.

“I lost my granddad…” Bottrill starts his explanation, then stops immediately. “I’ve got goose pimples now…” He regains his composure almost immediately, offers a brief, if unconvincing smile, and continues.

“He was the guy who brought me into cycling and showed me the ropes. He literally lived 200 yards away from me. I saw him every day. When he died, I was like: ‘I’m going to do this for you.’ I trained so hard.

“When I talk about mindset, I’ve been to some dark places, but in 2014, I was invincible. No one could touch me. It was for him. In 2014, I won every race, except the British nationals, which Wiggins won, and I think I was fifth. But in every other race, I was breaking competition records.”

REACHING THE PINNACLE

Pause for a moment to consider the magnitude of Bottrill’s achievement. The only men able to beat him were professional riders, racing at the highest level, paid handsomely to do so, and who enjoyed the support of well-funded teams competing in the elite UCI WorldTour. Bottrill, a father of three and a postman, had just eight hours a week to spare for training.

There’s a David and Goliath aspect to his story which gives it a broad appeal, even if more detailed knowledge of Bottrill’s career offers a different (and arguably more interesting) analysis: one focussed on the margins that separate Tour winners from exceptional amateurs.

"In 2014, everyone was looking at the guy who trains eight-hours-a-week and can compete with the pros."

Bottrill was once on an identical path to Wiggins. The vagaries of sport can be cruel, even if Bottrill is now sufficiently philosophical to celebrate his successes, rather than rue the missed opportunities.

He states no more than the truth when he says that his victories, and the competitive intrigue generated among his rivals, changed time-trialing in Britain. An amateur rider does not come close to defeating the professionals without a host of other amateurs taking a keen interest in his progress.

“You ask how time-trialing has changed, but I really think that’s something I achieved in the sport. In 2014, everyone was looking at the guy who trains for eight-hours-a-week and can compete with the pros. Everyone was asking: ‘What the heck is this dude doing?’ People started looking at my position on the bike, everyone started to copy it, and that’s how the sport has got to where it is now.”

Having revolutionised British cycle sport’s first and still defining discipline, Bottrill at last found his hunger for victory satisfied. Success, which for so long had eluded him, became routine. The wins were often accompanied by competition records, many of which still stand. He set up a coaching business. The next phase of his career beckoned.

“In 2014, I’d reached the pinnacle. I won every race, set competition records for the ‘25’, and the ‘50’ record is still there. Where do you go from that point? All your life, you’ve waited, and you’ve not just done it, you’ve done it better than any has ever done. The amount of races I won that year, and the number of championships, is still a record now. It was unbelievable. Then I set up the coaching business, and it just went crazy.”

COACH PARTY

“If you’d told me 20 years ago that I would be coaching world class athletes, I’d probably have laughed at you,” Bottrill says, unable to keep an incredulous smile from his face. “I can’t believe how things have grown since 2014.”

We’re enjoying our first decent coffee of the day in the compact surroundings of Bottrill’s coaching base, a tiny unit in a small industrial facility on the outskirts of Coalville. The East Midlands town is an unassuming place, dominated by the giant machinery at the heads of pits long since closed by the Thatcher government.

"That's why I can coach at the level I can, because I have to become the athlete, and process every element. I had to become Tim Don, if you know what I mean."

The location is hugely significant. Bottrill grew up in Coalville, learned his trade with the Coalville Wheelers, and returned there after a season in France, ready to settle down with Kate, now his wife, and the mother of his three children. He lives on the outskirts of the town, but spends long hours at the unit.

“Three years ago, I used to come here and hand in the mail,” Bottrill explains, gesturing at a room that is part pain cave, part office and part workshop. There’s an unmistakable sense of purpose, contained within the rack of Park Tools, the spare tyres and helmets neatly arranged on the wall, a selection of saddles, and a modified WattBike that looks especially adapted for the purpose of delivering maximum pain.

He believes that the separate skillsets of rider and coach are complementary, to say the least. The phrases ‘control freak’ and ‘obsessive’ occur regularly as Bottrill describes his approach, but his admissions come with a rueful grin that acknowledges these traits as weaknesses; flaws he is powerless to correct.

“That’s why I can coach at the level I can, because I have to ‘become’ the athlete. You have to process everything; you can’t just set the training. Setting a training programme is so easy. I could do that now, with my eyes closed. I’ve got to become Tim Don, if you know what I mean. I’ve got to work out every element of his mindset and the set up on his bike. You’re almost living it with them.”

THE YEAR OF THE DON

If 2017 was ‘Year of The Don’, then it was also the year of Bottrill the coach. Having hit his own high as a rider three years earlier, Bottrill takes an obvious pride in his assistance to a triathlete, who like his coach, discovered new methods late in his career to produce his best performances, when lesser competitors might have considered retirement.

The twist in Don’s tale is that he combined annus mirabilis and annus horribilis in the same season. Knocked from his bike on Kona’s Queen K Highway, just three days before the Ironman world championships, a broken neck deprived him of the chance to fulfil his status as pre-race favourite for the most significant event on the triathlon calendar. Having broken the Ironman world record in May, he would surely have started as favourite to lift his first Ironman world title.

"I'dlooked closely at Tim, and followed his transitions. He's the same age as me. I thought: 'This dude should be smashing it in Ironman."

Don’s comeback from injury (see the @tri_thedon Instagram account for astonishing footage of him riding a stationary bike in a gruesome Halo neck brace) proved that the West Londoner had the grit required to lift the biggest prize in the sport, but his incredible season owed as much to coaching as determination.

“There is a lot of science involved,” Bottrill admits. "I’d looked closely at Tim. He’s the same age as me. I followed his transitions. I thought: ‘This dude should be smashing it in Ironman.’ I was quite amazed when I saw his training. It was good, but I thought, ‘There’s so much more that you can do.’ I saw all his numbers, and I said: ‘You can be the best in the world, Tim.’ I don't think even he believed it.”

The road was not easy. Bottrill, as a world class cyclist who had dabbled in triathlon, possessed a unique insight. Don, a formidable athlete, who had always placed the greatest emphasis on his run, was open to suggestion - to a point. Bottrill felt that the athlete wasn’t fully committed to his way of working. The missing piece of the jigsaw proved to be Don’s former coach, Julie Dibben, who challenged Bottrill to think outside of the box in a six-word text message: “How do you win an Ironman?”.

EMOTIONAL DRIVE

For all the science, training plans, and search for "synergy" between Don’s two coaches and three disciplines, the most important factor proved to be human influence. Bottrill admits to an all-consuming commitment to his clients (“We will not let you fail") and his relationship with Don provides compelling evidence of its effectiveness.

It’s a relationship that has spanned the boundaries of time and space, thanks to communication tools like Skype and training apps in which Bottrill can ‘read’ the subtleties of Don’s mood from his data. Numbers are only part of the essentially human business of coaching, however. Camaraderie, banter, and occasional honest exchanges of opinion remain the most important aspects.

"I want success for my athletes, whether it's Tim Don, or someone who wants to ride up a hill fast. When you achieve that goal, there's no better feeling."

“The emotional connection I have with Tim is like..I don’t know," Bottrill pauses and chuckles. “It’s more than I've ever had with any athlete. When he got knocked out at Kona, that hit me like a ton of bricks. I got quite emotional about it. You've been through so much of the process together, and because I’ve been to all these horrible places, I knew how Tim felt, and what he was going to go through.”

Bottrill confesses to “going crazy in my living room” while Don was busy breaking the world Ironman record in Florianopolis, Brazil (“Last year, they were calling it ‘The year of the Don’. Every race, we would go in, and win it, win it, win it. And as a coach, you live that process with him"). The reverse is also true: when his athletes fail to message him with their success or otherwise in events they’ve planned together, “...it drives me nuts. I’m on tenterhooks.”

“You can ask all the athletes I coach. I probably get too emotionally involved, but that’s why I work so hard. They send me a text, or an email, and I’m on it straight away. I want success for them. Whether it’s Tim Don, or someone who wants to go up a hill fast, when you achieve that goal, there’s no better feeling. It’s amazing.”

RIDER. COACH. MENTOR.

For those who complain that justice in this world is in short supply (this writer included), the knowledge that Matt Bottrill is now coaching and leading a team of gifted up-and-comers is heartening. Our day in Coalville concludes with a photo shoot and a series of brief interviews with three of Team Bottrill’s riders: George Fox, Oliver Bates, and Welsh time-trial champion George Evans - a talented trio.

A 40-year-old with precisely nothing to prove, one wonders where Bottrill finds the motivation to ride in the biting cold and driving rain of an unforgiving January day. The answer lies in the death of his mother, whose passing has inspired her son to return to road racing, after two years as triathlete.

"For a long time, I didn't have the need to win, but a lot has happened in the last six to eight months, and I want to race again, and to be faster than I was before."

“Last year, I lost my mum to cancer. My bike is my defence mechanism. That’s how I deal with emotion. I did my last triathlon in June last year. I did really well, but I couldn’t commit to the training. And my mum, before she passed away, had said: ‘You need to return to your bike. Go out there and give it another go, if you want to.’”

Bottrill has already announced his intention to race the Eddie Soens Memorial in March, a race he won 20 years ago. He will also target victories in the UCI Gran Fondo World Series, a highly competitive category with an impressive cast of retired professionals. He talks also of an attempt at the Masters Hour Record, but this is a story for another day. The biggest prize Bottrill can hope for is help with the grieving process. The bike, as ever, has not failed him.

“I started riding my bike and it’s helped a lot," he confides. “I didn’t have the need or the want to win, but a lot has happened in the last six to eight months, and I want to race again.”

'CRAZY FAST’ SUITS

We began by reflecting on cycling’s happy knack for bringing together those who have delivered memorable performances with those who have merely observed them. Few stand on ceremony in interviews; even Grand Tour winners or those who have broken the Hour Record (to speak only of Endura’s clan).

Twice, Bottrill’s life has been touched by grief. His career was derailed by a nascent coaching regime that he maintains was scientific in name only, but rather than dwell on what might have been, Botrill has twice reinvented himself: firstly, as an amateur able to carry the fight to the professionals, and latterly as a coach of rare commitment.

"Endura don't just look at a skin suit from a wind tunnel perspective, they consider every element, and that's what makes it crazy fast."

Bottrill’s insights have been pivotal to the development of Endura’s D2Z Encapsulator suit, a garment worn by Movistar Team and Cervélo Bigla to win countless time-trials in the men’s and women’s UCI WorldTour, and more national titles than one can shake the proverbial stick at. Only Alex Dowsett, who broke the UCI Hour Record in an early prototype of a suit that last year won a Eurobike Award, can claim similar influence.

“In 2014, the advantage that I had over everybody was that I was wearing Endura suits. Simon [Smart] rang me up and said: ‘I’m working with Endura. Would you be willing to be part of a test team?’ I said: ‘Of course. If it’s going to give me an advantage, I’m up for it.’ The advantage was massive; we’re talking ten watts.

“I’ve always been part of that development process, and we’re at the stage now where we’ve got these silicone suits [Silicone Surface Topography]. With Endura, they’re not just looking at this from a wind tunnel perspective. They want to know how the suit performs on the road. They want to know if it breathes. They’re looking at every element, and that’s what has made it into the suit it is now - crazy fast.”

THE ENCAPSULATOR

As Bottrill prepares to begin a fourth phase of his remarkable career, with a return to racing at the age of 40, Endura draws closer to a public release of the skin suit he did so much to develop.

The D2Z Encapsulator suit has, in some ways, been Endura’s worst kept secret: a garment that with every Hour Record, every WorldTour victory, every national title, every Eurobike award, sparks feverish interest among amateur time-trialists, who combine working and family lives with an obsession with speed.

"To have developed the Encapsulator suit with Matt, as well as with Simon Smart and Movistar Team, feels entirely fitting." - Pamela Barclay, Brand Director

Bottrill is their champion, the postman who broke national records seemingly for fun in 2014, and who carried the fight to the visiting professionals at the national championships each year, in clear and repeated demonstrations of what might have been, had he enjoyed greater support in the early stages of his career.

“Matt’s story echoes Endura’s in many ways,” says Brand Director, Pamela Barclay. “As a rider, Matt was the renegade outsider prepared to fight with the best time-trialists in the world.

“Even if our partnerships in professional cycling now give us a privileged position inside the peloton, we have not forgotten our roots. To have developed the D2Z Encapsulator suit with Matt, as well as with Simon Smart and Movistar Team, feels entirely fitting for a brand that began life on a kitchen table in Edinburgh.”

Indeed, there is an undeniably maverick quality in training for eight hours a week, when your closest competitors are contesting Grand Tours and Monument Classics. For those familiar with Bottrill’s story, and Endura’s, the roots of a mutual admiration are easy to identify.

Now 40, and prepared to “hurt” himself all over again, Bottrill will divide his time in 2018 between racing and coaching athletes as gifted as Tim Don, Rachel Joyce and Lucy Charles. He will call upon an insatiable drive to work and to succeed, as he leads his team of young riders, while bringing the best from a host of world class talents.

Footnotes Words by Timothy John. Images by Sean Hardy Coalville, Leicestershire, United Kingdom

© 2021 ENDURA